17 August 2022 | Tavistock, UK [David Wright]

While some people have always dreamed of warmer climes, and many Europeans enjoyed the heatwave this summer, I confess that I have always wanted to visit the frozen wastes of the Antarctic.

One reason is that, as a youngster, I remember my mum telling me that my grandmother used to have tea with the Wilson family in my hometown, Cheltenham. The son of the Wilson family grew up to be Edward Wilson the polar explorer- who died with Captain Robert Scott on their way back from the South Pole in March 1912. I also remember Wilsons statue – sculpted by Scott’s wife, Kathleen Scott, prominently displayed along Cheltenham’s Georgian promenade. When the famous ‘Scott of the Antarctic’ film was released, the local cinema offered all local schools to see the film for free. I remember going with my school – and being moved watching Captain Lawrence Oates saying, ‘I am just going outside and may be sometime’ before courageously walking to his death – in order to give his three companions a chance to survive. The tragic final scene shows the blizzard gradually covering their tent with snow. The occupants are not to be found until 8 months later, and only 11 miles short of their next supply depot.

The Endurance – Located Again After 107 Years

One of Captain Scott’s officers on his first expedition to the South Pole was a young Anglo-Irish man called Ernest Shackleton, who had to leave the trip early due to ill health. What he learned from Scott, however, about expeditions, logistics and leadership, would be put to very good use later in his life. Earlier this year in March, Shackleton’s famous ship – the Endurance was found, 107 years after, and just four miles from where it sank in November 1915.¹

Described by archaeologists as ‘the greatest shipwreck hunt ever undertaken’, the Endurance22 team used robotic cameras to find the wreck before sending divers down to take more detailed photographs -3000m down under surface ice 3m thick.

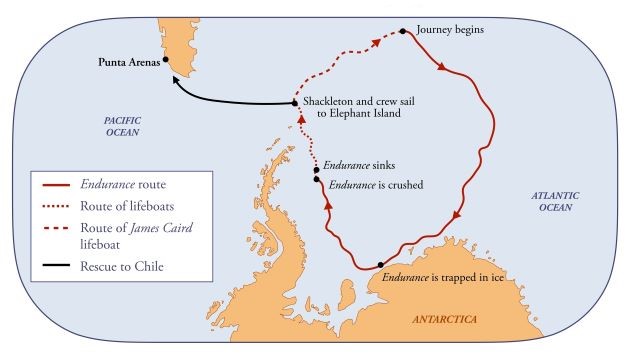

Shackleton was the leader of the 1914-1917 Imperial Trans Antarctic Expedition, when the pack-ice crushed his ship in the Weddell Sea and stranded him and his 27 men on floating ice, 150 miles from the nearest land.

Although the original expedition – aimed to be the first to traverse the entire Antarctic continent, proved to be a failure, it is still regarded as one of the supreme epics of polar exploration, the last great expedition of the Victorian ‘Heroic Age’.

Among outdoor leaders and adventurers Shackleton is still regarded as Britain’s greatest polar explorer – because even though his expeditions were not always successful, unlike others such as Scott, he never lost a man.

When Ernest Shackleton was recruiting for his crew in 1914, his advertisement in The Times received over 5000 applications – including from 3 schoolgirls! The ad read: ‘Men Wanted: for hazardous journey – small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful, honour and recognition in case of success.’

South

Shackleton and his 27 men left England in late summer 1914 and reached South Atlantic South Georgia Island in late October. Shackleton then struck out across the Weddell Sea – aiming to set up base from which to reach the South Pole using dogs. By January though, the sea had completely frozen over and had trapped their ship. Still using Endurance as a floating base, they drifted with the pack ice for nine months until the ship was squeezed so tight it sprang a leak. Lowering all their supplies and three small lifeboats onto the ice Shackleton and his crew abandoned ship to watch Endurance being crushed until it sank in November.

To improve their chances of reaching land, and with rescue not an option, Shackleton decided to march across the ice dragging their boats and supplies with them. After 6 brutal days in sub-zero temperatures and high winds they only managed 10 miles – set up another ice base called ‘Patience Camp’ and waited 5 months for the ice flow to take them to the open sea.

Now with dwindling supplies, Shackleton decided their best chance would be to try and reach Elephant Island – about 600 miles away across the sub-Antarctic Ocean. Using just the stars and basic navigation instruments they part rowed, and part sailed their open boats through mountainous waves and floating ice to try and land on the uninhabited island – named after elephant seals and smaller than the Isle of Man. Incredibly, they made a precarious landing in just seven days.

Still stranded, with supplies getting even lower, and the pack ice beginning to close in again, Shackleton decided to go for help. He leaves his second-in-command in charge, selects five men, loads one of the lifeboats with provisions and a small stove, and sets off on one of the most astonishing journeys of all time. 800 miles through mountainous seas, powerful currents, and storm force winds in a small open boat, back to South Georgia. He estimated it would take a month, knowing that if they missed, they would probably never be seen again. They did it in 16 days. That’s 800 miles in a straight line to hit a lump of land less than 20 miles wide!

‘It’s Not Good to Do That Kind of Thing Too Often’

They land in a hurricane only just avoiding capsize, but unfortunately, on the wrong side of the island – with the whaling station 30 miles away and 9,000-foot mountains in the way. Too exhausted to sail around the island, Shackleton decides to cross the island by foot taking with him his two strongest men and enough provisions for three days. That’s 30 miles over glaciers, crevasses, and ice-covered peaks when you are already exhausted. At one point and faced with one particularly impossible section, poor visibility, and too tired to cut ice steps, they sat on coiled ropes and managed to slide down a 3000-foot-high precipice, at about 60 mph, arriving miraculously at the bottom without any broken limbs. Shackleton’s wry comment was ‘It’s not good to do that kind of thing too often.’ They reached the whaling station in 36 hours on 20 May 1916. The next day Shackleton took a boat to rescue the three men he had left on the far side of South Georgia, and within three months had returned to Elephant Island to rescue the remaining 22 crew members who had all managed to survive.

Shackleton died of a heart attack on January 4th,1922 and is buried on South Georgia. The reason for sharing this incredible journey with you will, I hope, now become apparent.

Even the Bible Was Left Behind…

When the Endurance had sunk, and it had been decided to drag the three lifeboats across the ice towards the Atlantic, only the barest essentials could be carried. Even the Bible given to the ship by Queen Alexandra was left behind. Shackleton however tore two pages out and carried them with him for the remainder of his journey. One was the Bibles’ fly leaf on which was a handwritten message from Alexandra which read, ‘May the Lord help you to do your duty and guide you through all the dangers by land and sea. May you see the works of the Lord and all his wonders in the deep’.The other was a page from Job which records God answering Job out of the storm in chapters 38 and 39. In his book, South, Shackleton highlights two specific verses which he described as ‘wonderful’. ‘Out of whose womb came the ice. And the hoary frost of heaven, who hath gendered it? The waters are hid as with a stone, and the face of the deep is frozen (Job 38:29–30).

While it is not clear that Shackleton was a Christian, having a reputation as both ‘a drinker and a womanizer’. It’s clear, however, that his determination not to lose the life of any crewmember demonstrates he was a caring man. His use of the word ‘Providence’ – with a capital ‘P’ in his travel journals – also showed that he acknowledged God’s guidance in his life.

Another Person With Us?

After that daunting 800-mile small boat journey when a crewmember always remained awake to bail seawater and remove the 15-inch-thick ice that formed …. and after that equally impossible, dangerous, mountain trek across South Georgia, he wrote:

‘When I look back at those days, I have no doubt that Providence guided us, not only across those snowfields, but across the storm-white sea that separated Elephant Island from our landing-place on South Georgia. I know that during that long and racking march of thirty-six hours over the unnamed mountains and glaciers of South Georgia it seemed to me often that we were four, not three. I said nothing to my companions on the point, but afterwards Worsley said to me, ‘Boss, I had a curious feeling on the march that there was another person with us.’ Crean confessed to the same idea. One feels ‘the dearth of human words, the roughness of mortal speech’ in trying to describe things intangible, but a record of our journeys would be incomplete without a reference to a subject very near to our hearts.’

Shackleton was to later write “We had seen God in His splendours, heard the text that Nature renders. We had reached the naked soul of man.” It’s clear that Shackleton knew what it was like to sense Gods presence!

Michael Obel, a Presbyterian minister in Pennsylvania, wrote this about God as Providence:

“Providence is the medium of our existence. There never has been and never will be as much as a single nanosecond of any person’s life that is not submerged in the infinite holiness, wisdom, and power of the Creator who preserves and governs us. Perhaps it’s understandable that we humans take providence for granted.”

On Friday 20 May 2016, a centenary service of thanksgiving was held at Westminster Cathedral in memory of the courage and endurance of Sir Ernest Shackleton and his men. It was conducted by the Bishop of London and the Dean of Westminster, and attended by many dignitaries, including Princess Anne – as the Patron of the Antarctic Heritage Trust. The main scripture reading came from Joshua 1, verses 1-9. “Be strong and courageous, do not be afraid; do not be discouraged, for the Lord your God will be with you wherever you go” (NIV, emphasis added).

[Photos: Unsplash, Shutterstock, Moody Publishers / CC BY 4.0]

¹Source: BBC News.