06 September 2023| St. Albans, UK [David Neal]

It is a picture that speaks volumes! A parish church in the small English village of Blundeston, Norfolk, located between the East Anglian UK coastal towns of Lowestoft and Great Yarmouth. Within three miles, there are four other similar churches. I have walked around this church many times, at different times of the year, usually early morning. But recently, I decided to go for an evening walk.

And there it was, standing as it has been for a thousand years, surrounded by freshly harvested fields, this time in the evening dusk. One light shines dimly through a window. I imagine the congregation size to be between 25-30 people. It would have been packed to capacity in former times, as would all of the four surrounding churches.

If you want to know the mission reach of the Church of England (C of E) – it is simple and straightforward:

“The Church of England seeks to be a Christian presence in every community, up and down the land.”

But that the C of E is struggling to fulfil its mission is no secret. And as I saw that brightly lit cross on the round tower, it spoke to me as a message of defiance. No doubt placed there as a recent addition, it is as if it says, “You may think the light of the gospel – and the glory of the cross in this country is about vanish, but we’re still here to remind you that this a light that can never go out!”

“Britain is no longer a Christian Country, say front-line clergy.”

For the first time in a decade, the 29 August headline by The Times reveals clergy attitudes. With only 46.2% of UK citizens describing themselves as Christian in the 2021 census (down from 53.9% in 2011), foreboding over the future of the C of E has become a national pastime. In 2013, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, George Cary, warned that the church could be “one generation away from extinction.” Whether a self-fulfilling prophecy or not, the current cohort of Anglican clergy believe it to be still heading in that direction, with 66.7% expecting church attendance over the next ten years to fall from a 2019 pre-pandemic level of 690,000. A further 31.9% believe that “The Church of England could face extinction if the decline continues.”¹

As the national church, the C of E is under increasing pressure to adapt and change to the attitudes of society. Reflecting the mood of most UK Members of Parliament (MP), Labour MP Ben Bradshaw said, “It is unsustainable for the state church to be out of sync… with the society, it aspires to serve.” For the clergy on the frontline, doctrinal issues are live as they wrestle with how to apply the church’s teaching against the prevailing attitudes of the citizens in their parish where they pledge to be present.

In their book “That Was the Church That Was”, Andrew Brown and Linda Woodhead make the case that “The Church of England is lost because the England of which it was the church has disappeared.” Not least because the “English Heritage Christianity” with its vision of a “lovely church in a lovely village” is over.²

Is Decline Inevitable?

From the Adventist perspective, it would be easy to conclude that neither benefits the other when church and state are institutionally joined at the hip. And while it is the case that the C of E was launched due to ‘exceptional circumstances’ (Henry Vlll split from Rome 1534), most denominations go through a life cycle of “start, grow, thrive, decline and eventually end.”³

It’s worth taking a moment to remember how Christianity started as a movement. It was a radical, alive, expectant movement with God visibly at work, doing great and mighty things through the apostles.

‘When the day of Pentecost arrived, they were all together in one place. And suddenly, there came from heaven a sound like a mighty rushing wind, and it filled the entire house where they were sitting. And divided tongues as of fire appeared to them and rested on each one of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit gave them utterance’ (Acts 2:1-4, ESV).

While the Day of Pentecost was the launch of the Risen Christ movement, and its followers ‘all filled with the Holy Spirit’, less than sixty years later (AD 90), John the Apostle describes some movement followers in the region of Laodicea as ‘lukewarm’ (Revelation 3:14-22) – a far cry from their supernatural and sensational beginning. By AD 260, ‘Risen Christ’ followers were all but divorced from their roots, with the ‘gift of the Spirit’ a tradition and now the ‘official possession of the clergy, especially of the bishops’.° The shift from movement to denomination was underway.

Seventh-day Adventist pioneers saw themselves as movement people. They believed their purpose was to restore the distorted message of Christianity, a recovery helped along the way by the Protestant Reformation. Believing a return to biblical faithfulness was more than necessary because of Christ’s soon-to-be-fulfilled Second Coming, they felt theirs was a mission and message given directly from God. The movement mindset was the wind in their sails, and they would give their all for it. We know the story well.

What if it is possible to maintain the characteristics of those in the ‘Risen Christ Movement’? Does Adventism still have ‘movement-like’ values, or have we inevitably morphed into denominational thinking – and practice? The question is critical because it determines not only how we see ourselves and others but how we also connect with the community around us.

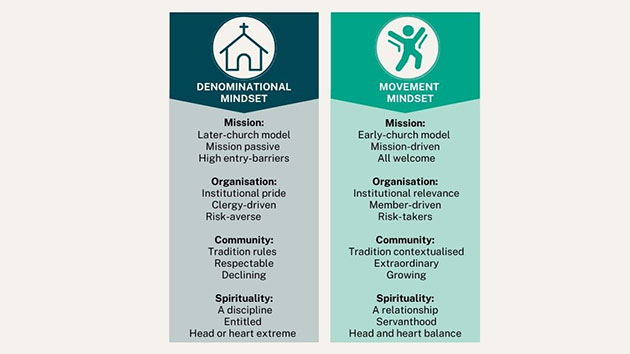

The challenges facing the Church of England challenged me to look at the life cycle of organisations (particularly the church) and apply it to the Adventist context. Do you see what I see in the areas of mission, organisation, community, and spirituality?

These characteristics are made without judgement of any organisation or person. They are neither comprehensive, nor absolute and in some cases interchangeable. We may or may not agree with the contrasting mindest. That’s not a problem, because the real intent is to help us think prayerfully and biblically about the nature of the church. What would our local church look like if we have more of a movement than denominational mindset? How would our unions and conferences look like? The same question is relevant for all levels church life, and for that matter any church institution. Worth reflecting on at a prayer meeting, small group, and even a committee meeting.

But, would it not be an unholy disaster if Adventism in our lands were shaped more by the mindset of the left-hand column rather than that of the right?

What does Christ say about his relationship with the church?

As much as Ephesians 5:21-33 refers to Christ’s vision for Christian marriage, Paul says, “There is a secret truth revealed in this scripture, which I understand as applying to Christ and the church” (5:32 GNB).

The ‘secret’ and wonderful truth is:

- Christ is the head of the Church, gives leadership, and has authority over it.

- He loved the Church – went all out in his love for it – through giving, not getting.

- The Church is His body, of which he is the Saviour, making it whole and complete.

To make the church radiant in glorious splendour

To bring the best out in her.

To feed and care for her.

To make her holy.

To treasure her.

“I thank my God in all my remembrance of you, always in every prayer of mine for you all, making my prayer with joy, because of your partnership in the gospel from the first day until now. And I am sure of this, that he who began a good work in you will bring it to completion at the day of Jesus Christ.” (Philippians 1:3-6, ESV.)

With that promise – how could the light and glory of the cross of Christ in ever flicker and go out – the UK or anywhere?

¹Britain is no longer a Christian Country say front-line clergy, The Times, 29 August 2023. ²That Was the Church That Was, Andrew Brown and Lisa Woodhead, Bloomsbury Continuum, p. 219 and 222. ³ The Church Lifecycle: A Comprehensive Guide, The Unstuck Group, 3 April 2013. ° A History of the Christian Church, Williston Walker, Simon and Schuster, p. 11. [Featured image: David Neal]